- Details

Medieval and early modern Kłodzko benefited from the dozen or so public and private wells located within the town walls and on Castle Hill (where five were in use, the oldest Church Well dating back to 1393 and the deepest Baker’s Well reaching around 60 m down). The greatest demand for the water from these wells came from the food industry (particularly brewery). The poor townsfolk usually drew water for consumption purposes.

Given the geological structure of Kłodzko, constructing a well (or more appropriately cutting it out) was a difficult and time-consuming undertaking, particularly in the higher parts of the town.

A local legend refers to the construction of Church Well on Castle Hill, which is attributed to a certain shoemaker named Czesław. The persistent craftsman was able to cut out a 2-metre wide well reaching the depth of around 30 metres over the course of nine years. His daily diggings would fit in his leather shoemaker’s apron. The water was drawn from this well with a paternoster, a device named after the prayer, which took as long to say as the process.

The significance of the town’s traditional wells declined with the development of the water pipeline system in 1540. This system would feed water to the wells, which now served as intake points.

As the only reliable sources of life-giving water, the wells were guarded and protected, particularly at times of war. Private wells were surrounded with fencing in order to restrict outsider access.

Nevertheless, according to legend, Baker’s Well, which was located in the fortress developments on Castle Hill, was poisoned in 1806 by one Charlotta Ursini, a resident of Kłodzko and supporter of the Napoleonic army then laying siege to the city. By inflicting a stomach disorder and general malaise upon the garrison, she allegedly prompted the surrender of the Prussian soldiers to the invading French forces.

Another legend concerns the poisoning of numerous wells in the year 1622, when Kłodzko was besieged by the Imperial Austrian Army. The only sources of clean water were underground private wells, which included those owned by the wealthy merchant Honza and the rapacious baker Ernest. The baker sensed a business opportunity and began selling the water from his well. Honza, moved by the misery of the townsfolk, gave his away for free. The greedy Ernest was not impressed by the merchant’s generosity and demanded that everyone buying his bread should also purchase his water. Needless to say, this story did not end well for the baker...

* source: Romana and Leszek Majewski, Legends and Stories of the Kłodzko Land part 1, Kłodzko 2008, p. 40 and 56.

Public executions were performed in Kłodzko from the Middle Ages through to the 19th century. The fixed gallows in the town signified the privilege of punishing with death those who acted against the law and moral principles. The last execution occurred in 1850. The executioner beheaded, with an axe, an individual by the name of Treutler, for the murder of a peasant from Drogosław.

Punishments were carried out at the gallows outside the town, on the road to Złoty Stok, and at the pillory, or whipping post, in front of the Town Hall. The pillory appeared in the local sources in the years 1551-52 and was supposed to have been topped by the figure of a peasant with a sack of grain. Raised beside the pillory was a wooden scaffold upon which the condemned were killed by beheading with a sword.

The records of the town of Kłodzko speak of a number of punishments, of hanging, beheading and breaking with the wheel, being dragged to the execution site and impaled, of tearing with pincers and burning, being laid on the wheel, burial alive, quartering, and beheading combined with the driving of a stake through the heart.

In the 17th century, 60 local settlements were punishable by the facilities of Kłodzko.

From the Middle Ages through to the modern era, beer was a staple beverage in the towns of Lower Silesia. Water, often polluted, could cause illnesses of the digestive system and carried microbes. Beer, far weaker than it is today, was considerably safer. Everyone drank it – adults and children alike – and it was served even to patients in hospital buildings. Beer drinking was also permitted in periods of fasting. It is estimated that average daily consumption of the alcoholic beverage was at this time around two litres per person.

The barley and wheat beer of Kłodzko was well known in Silesia for its outstanding quality, and its production in the town, by malters and brewers, was an important and common occupation. The privilege of brewing beer was regulated by local law. In the Middle Ages, this privilege was held by c. 200 houses in Kłodzko. In the 15th century, a special council appointed by the municipal councillors was involved in checking the scale on which beer was being produced beneath the buildings of Kłodzko, and whether this accorded with the amount in the privileges. This information is a source which confirms that the underground chambers were used not only as spaces for storing beer, but also as malt houses.

The appearance of the office of executioner should be associated with the development of the judiciary and the first codes of German law. The earliest mentions of the professional executioner appear in the sources in the 13th century, but the professionalization of the role and the regulations associated with it underwent a slow evolution. The duties of the executioner, consisting initially in the infliction of corporal punishment, were extended over time to include the performance of cruel tortures, along with many other functions seen as ‘dirty’ in nature. The executioner was to maintain the torture chamber, its lighting and the instruments, as well as the technical condition of the penal fittings in the town, watch over the execution sites and the condition of the bodies displayed publicly following execution, see to cleanliness in the municipal prison, clean waste from the streets and supervise the brothel. This final function, seemingly administrative, was in fact sanctioned pimping and procuring.

The Profession of Executioner

The executioner received regular pay from municipal funds and benefits in kind. Not every town could afford to maintain its own executioner, however, in which case attempts had to be made to borrow one from a more affluent centre.

How efficiently a sentence was carried out depended in large measure on the will power, ability and favour of the municipal executioner. Obtaining the qualifications of master executioner required an apprentice to study under an independent and experienced individual. The period of study lasted many years, beginning in the case of the son of an executioner at an early age. The chief demands made of those pursuing the profession were an excellence in the act of killing, flogging, branding and severing limbs, as well as in torture, but also in the later treatment of injuries. The executioner paid for sloppy work with his career, and sometimes in health or with his own life.

The Executioner & Other Residents of the Town

The burghers held themselves aloof from the executioner, the ‘dirty’ nature of the profession bringing with it a social alienation. The presence of the executioner among the ‘decent citizens’ was undesirable, and this applied to both church and tavern. Executioners also grew rich relatively quickly, which only compounded the dislike. The house of the executioner was found on the outskirts of the town, often close by the residences of the dog catcher and gravedigger, and the brothels. This social ostracism and restriction of social functions affected the entire family, making the profession of executioner in a certain sense a hereditary one. Even marriage occurred among executioner families, leading to the appearance of whole executioner clans.

The Executioners of Kłodzko

In the 16th century Kłodzko was the sole town in the region to employ its own executioner. The first of these known by name and surname, Lorenz Volkmann, appears in the local sources c. 1569.

Of the executioners of Kłodzko, one of the most famous was Christopher Kühn, who in the mid-17th century, beyond the place of torture in Kłodzko, held also a Meisterei in Wambierzyce and Radków, and possibly in Otmuchów, the home of his wife, Anna Catharina Hildebrandt, who was the daughter of the executioner there. According to the sources, Kühn himself chose the path of the criminal, and failed to abide by the orders of the municipal authorities of Kłodzko.

Local sources claim that the executioners of Kłodzko were also involved in the provision of medical services, bringing protests from the local barber-surgeons, who accused the executioners of botched work. As a result, the municipal authorities dismissed both Christopher Kühn and fellow executioner Hans Gottschalk.

- Details

Sister cities are a form of an agreement between cities in various countries aimed at cultural, commercial, and informational exchange. Sister cities focus on human cooperation beyond state borders. Sister cities are often initiated by the personal communication of their residents. The partnership is established with the signing of the appropriate partnership document by both parties. The most important premises of such partnerships include cultural exchange, sharing of experiences, launch of joint cultural, sports, and social initiatives, cooperation in education, development of tourism, and mutual promotion. Please visit the websites of Kłodzko’s sister cities to learn more about their features and current cultural and tourism offers.

RYCHNOV

The partnership agreement between Kłodzko and Rychnov nad Kněžnou was signed officially on 06.12.2008.

BENSHEIM

The partnership agreement between Bensheim and Kłodzko was signed on 17 June 1991

NACHOD

The agreement between Nachod and Kłodzko was signed in 1995

CARVIN

Carvin is Kłodzko’s oldest partner town. The partnership agreement was signed on 10 May 1980

FLERON

The partnership agreement was officially signed on 22 May 1997 during celebrations of the Kłodzko Holiday

RĂDĂUȚI

The partnership agreement was officially signed on 12 August 2017 during celebrations of the Kłodzko Stronghold Holiday.

LIMANOWA

The partnership agreement was officially signed on 21 July 2018 during celebrations of the Limanowa Holiday

- Details

Kłodzko is one of the most beautiful cities in lower Silesia. It has a rich history dating back over 1000 years, which includes Czechs, Germans, and Poles. These three cultures were what determined the city’s growth, economic and social life, form, and nature. The amazing architecture, historical monuments, works of art, magical locations, and contemporary events combine to form the current unforgettable atmosphere of Kłodzko – a hospitable, open, and friendly city. Come to Kłodzko!

The city limits are as follows:

- the northern city limits are designated by the location where the Ścinawka river discharges into Nysa Kłodzka river

- the eastern city limits drop down into the Jodłownik valley on the border of Mariańska Dolina and Wojciechowice, continue along the ridge of running from Kłodzka Mountain in the Bardzkie Mountains to Owcza Mountain, and culminate in the Jaszkówka valley on the border with Jaszkow Dolny

- the southern city limits run along the ridge of the distinct bench of the Nysa Kłodzka Valley to the mouth of Biała Lądecka, from there southwest down the Czerwoniak slope to the Bystrzyca Dusznicka valley on the border of Stary Wielisław and Książek, and up the Bystrzyca Dusznicka to Zagórze.

- the western city limits run along the expanse plateau near Mikowice to Leszczyny

Kłodzko is a prominent rail and road hub. The city offers direct train and bus connections to all major Polish cities.

Major roads:

- national road no. 8 ( Wrocław – Kłodzko- Kudowa),

- national road no. 33 ( Kłodzko- Międzylesie),

- national road no. 46 (Kłodzko- Opole),

- national road no. 381 ( Kłodzko- Wałbrzych)

Nearest airports:

- Wrocław (80 km),

- Praga (220 km),

Nearest border crossings:

Vehicle border crossings

The Kłodzko Poviat has three road border crossings with the Czech Republic open to international traffic.

- Kudowa Słone - Nachod

- Boboszów - Dolna Lipka

- Tłumaczów-Otolice

Rail border crossings

There is one border crossing available for international rail traffic in Międzylesie on the Wrocław - Praga trunk line

Pedestrian border crossings

The Kłodzko Poviat also offers numerous pedestrian border crossings open to tourists.

- Details

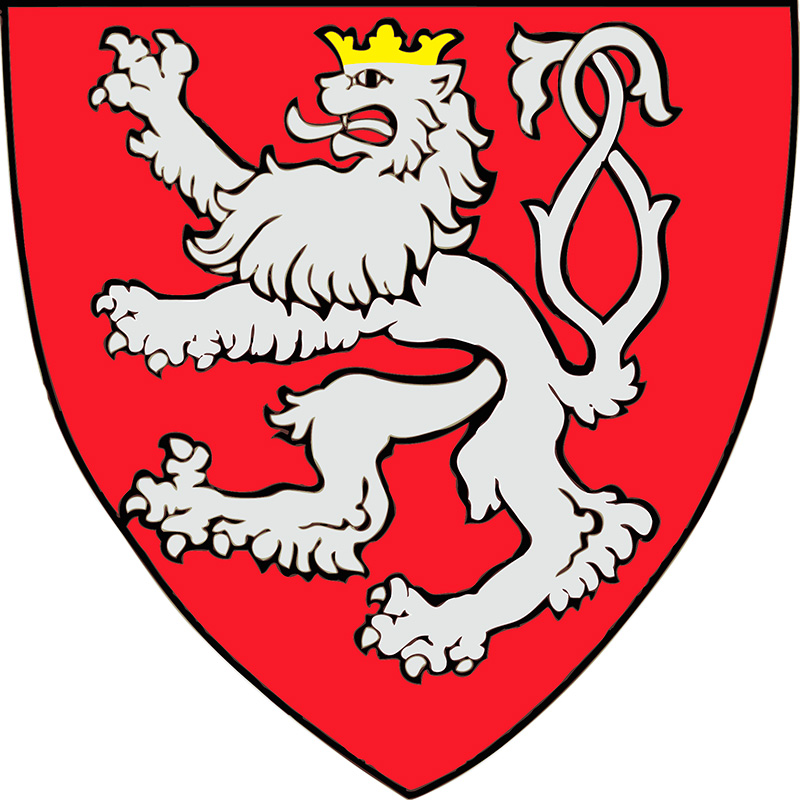

The coat of arms of Kłodzko depicts a white Bohemian Lion with two tails wearing golden crown on a red background. According to tradition, it was granted to the city by Premyslid King Ottokar II between sometime between 1253 and 1278. It is the oldest symbol of the city, dating back to the middle ages. We do not know the exact date, because no incorporation documents or copies thereof have been preserved.

The coat of arms of Kłodzko depicts a white Bohemian Lion with two tails wearing golden crown on a red background. According to tradition, it was granted to the city by Premyslid King Ottokar II between sometime between 1253 and 1278. It is the oldest symbol of the city, dating back to the middle ages. We do not know the exact date, because no incorporation documents or copies thereof have been preserved.

The lion with two tails is a replica of the coat of arms of Bohemia, of which the Kłodzko Land was a part at the time. The capital of the Kłodzko Land held the statute of royal free city. Another city in the region – Bystrzyca Kłodzka – has a similar coat of arms. The earliest preserved image of the lion is on the Seal of the City of Kłodzko, which dates back to the third quarter of the 13th century.

Legends about the coat of arms

- According to the first legend, after the city was incorporated by King Ottokar II of Bohemia, the people of Kłodzko decided to travel to the royal court in Prague to ask the king for a coat of arms, which was the highest determinant of urbanity in the middle ages. The king received the messengers and decided to grant Kłodzko a coat of arms presenting a lion wearing a crown. As the stone statue of the lion was on its way to Kłodzko, an accident occurred and it fell out of the wagon. The tail broke off. The messengers travelled back to Prague and received a new statue with the coat of arms, the difference being that the sculptor made the lion with two tails this time, just in case. This time, the statue arrived in Kłodzko in one piece. Consequentially, the lion has two tails.

- The second version says that King Ottokar II gave the coat of arms with the lion to the city as thanks for its loyalty, but the court painter hurriedly painted the lion without a tail. When the painting was sent back to the king, he ordered that the lion receive two tails as compensation.

- According to the third version, the messengers from Kłodzko were attacked by highwaymen on their way back. In the ensuing battle, the tail of the stone lion inside the crate broke off. The messengers returned to the court of King Ottokar II to ask for a new coat of arms. The ruler was understanding and gave them the coat of arms, which was supposed to be placed on the Malostranska gate in Prague. And so, the city received a coat of arms with a lion wearing a crown and with a forked tail.

The coat of arms of Kłodzko, which presents a lion, was given to the city by Ottokar II of Bohemia as a gift for the strength and persistence frequently demonstrated by the city. However, the lion arrived in the city without its tail. The city requested permission for repair. The king decided that in exchange for the missing tail the lion would now have two.

The flag of Kłodzko consists of two horizontal stripes: yellow and red. It was established by the City Council in 1990 and is displayed during local celebrations and meetings with partner towns.

The flag of Kłodzko consists of two horizontal stripes: yellow and red. It was established by the City Council in 1990 and is displayed during local celebrations and meetings with partner towns.

The current bugle call dates back to 1998 and was written by Stanisław Dąbrowski.

- Details

A visit to Kłodzko is an opportunity to see many of its historical sites and participate in cultural, sports and leisure events organised throughout the year across many different locations such as the market square, the square under St. John’s Bridge (access from Daszyńskiego or Matejki Street), Strażacki Park (Traugutta Street), and the stadium (Kusocińskiego Street) and the Kruczkowskiego housing estate.

- Details

Kłodzko is the oldest and biggest city in the Kłodzko region. The city’s development and prominence benefited from its strategic location between the Nysa Kłodzka valley and the Fortress Hill (369 MASL). In the medieval era, it served as a trading and defensive communication centre. The history of Kłodzko is made up of the history of Czechs, Germans, Poles, Catholics, Protestants, Jews, craftsmen, merchants, monks, and soldiers. Over the centuries, Kłodzko was home to multiple cultures, religions, and professions, It was able to evolve into one of the most beautiful cities of Lower Silesia and the cultural and tourist centre of the Polish and Czech borderland.

The first records of Kłodzko date back to the Chronicle of the Czechs by Cosmas of Prague, who writes about the death of Saint Adalbert’s father, Bohemian duke Slavník, owner of a gord named Kłodzko located on the Nysa river, in the year 981. However, according to archaeological findings and historical sources, the gord must have existed long before this time on the amber road connecting Bohemia and Poland.

In the 11th century, Kłodzko was the object of frequent Polish-Bohemian disputes and would be bounced back and forth every few years between the Piasts and the Premyslids. In 1114, the wooden gord was burned down completely by Bohemian duke Sobeslav, who would rebuild it partially with brick in 1129. On 30 May 1137, under the power of the peace treaty, Boleslaus III the Wry-mouthed released Kłodzko to Sobeslav and the town would remain under Bohemian administration for the next few decades. By 1200, the town had expanded from being just a gord and now had a market, market settlement, two churches, and a hospital. The town the town was granted German city rights sometime between 1253 and 1278 by Premyslid King Ottokar II of Bohemia; the oldest preserved document with the city seal dates back to the year 1305. In the 14th century, Kłodzko suffered numerous cataclysms: epidemics, fires, and floods, the most severe of which occurred in 1310 and produced over a thousand casualties. Despite the hard times, the city was also experiencing an economic boom, mainly because it had been granted further privileges. At this time, Kłodzko had one of the best schools in Silesia, a monastery library, and over 30 growing crafts guilds. The Hussite Wars came in the early 15th century. Kłodzko was able to resist the Hussite attack in 1428 but was conquered in 1453 by Hussite King George of Podebrady, who elevated the Kłodzko Land to the status of sovereign county in 1459.

Kłodzko thrived in the 16th century but again suffered from frequent floods and fires. In 1526, the city was taken over by the Habsburg dynasty. The most noteworthy individual of the era (from 1549) was Ernest of Bavaria. By the second half of the century, there were 275 estates in midtown, including numerous brick renaissance tenements. Before Kłodzko was turned into an arena of the Thirty Years' War between Protestants and Catholics (1618-1648), the majority of its population was protestant. In 1622, after a long siege, Kłodzko was captured by the army allied with catholic King Ferdinand II. The city was destroyed and many people were killed. Kłodzko was doomed to decades of deep economic crisis. However, the education, culture, and intellectual life continued to thrive thanks to the Jesuits, who had been brought back to the city.

The next important era in the city’s history was the First Silesian War (1740-1742) between Austria and Prussia. Frederick II the Great was victorious in the dispute over Silesia and thus the Kłodzko County was turned under Prussian administration for over 200 years to come in 1742. Kłodzko became a garrison town and the whole fortification system and fortress were expanded and reinforced with measures like the donjon. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), despite the excellent defensive system, the fortress was surrendered to the French army led by Jerome Bonaparte in June of 1807 after months of battles. However, grand politics would determine to keep the city under Prussian administration. In the second half of the 19th century, Kłodzko successively started to expand far beyond the city walls as it was no longer strictly military in nature. This period included construction of the waterline system (1886), the railway (1874), the prison (1887), and the court (1897). This era of development was stopped by World War I and the subsequent interwar crisis, but the life in the out-of-the-way city continued rather normally, even in times of global crises.

During World War II, the Kłodzko fortress was used as a prison to torture prisoners of war and German deserters. In 1944, it was also used by AEG as an arms factory, which manufactured components for U-boats and V1 and V2 missiles. On 2 June 1945, Kłodzko was taken over by Polish administration and most of the German population was displaced. The most important events of the post-war era include the rescue of the Kłodzo Old Town during the years 1958-1976 and the “millennium flood” in 1997, when heavy rainstorms forced the water of the Nysa Kłodzka River to rise by over 8.7 metres above its standard level on the night of 7 July and destroy many buildings, particularly near Sand Island and in the eastern part of the city.

Many of these events have left marks on Kłodzko that are still here to this day. They may not be readily visible, but we can feel the city’s 1000-plus year history pretty much everywhere.

Did you know:

- according to certain sources, the Sankt Florian Psalter – one of the oldest preserved Polish manuscripts – was created in 1398 in Kłodzko

- John Quincy Adams, who would go on to become the sixth president of the United States, visited Kłodzko during his journeys of Silesia

- beer brewing was an important trade in Kłodzo; in 1410, 190 homes were authorized to brew beer and there were 8 breweries operating in the city until 1945

Notable people:

- Saint Adalbert (956-997) – his father Slavník was the owner of Kłodzk in the 10th century

- Ernest of Pardubice (1297-1364) – first Archbishop of Prague, founder of the Charles University in Prague, born and buried in Kłodzko

- Anna Zelenay (1925-1970) – Kłodzko poet

- Emil Czech (1908-1978) – Polish soldier, played St. Mary's Trumpet Call on the day of the capture of Monte Cassino on the rubble of the monastery in 1944

English

English  Polski

Polski  Deutsch

Deutsch  Český

Český